Let’s be honest — data governance can be tough. To begin with, it’s an over-loaded term. It means different things to different people. As a result, far too many programs struggle to get traction or worse yet, falter only to be relegated to the heap of corporate process improvement fails. Sometimes these failures take the practitioner’s career with it. Not for lack of effort, but rather it’s a side effect of how incredibly difficult it can be to associate policies, classifications, metrics and other programmatic aspects of data governance with the actual data. This is a metadata problem to be sure.

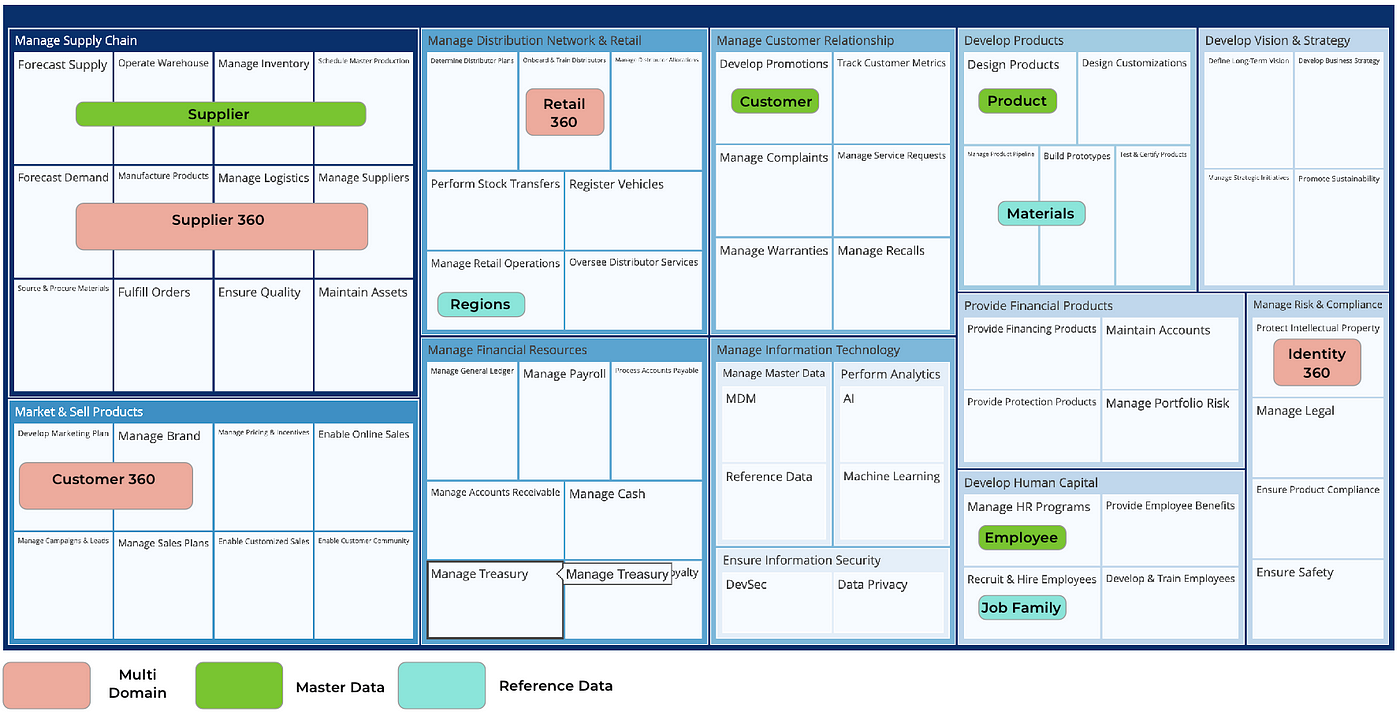

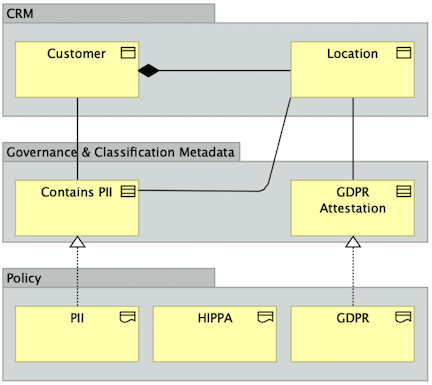

When reviewing the role of metadata within a given data architecture, associating various aspects of a meaningful governance approach is compounded by the broader challenge: Large data ecosystems can be complex, and it can be nearly impossible to bulk modify source data schemas to accommodate the governance meta-model. Modifying each of the source systems in order to store new or additional metadata would require multiple changes (new columns or tables, file formats etc), testing, and in some cases “rewiring” integration points or even APIs. Even if you’re able to get this done, you would then face the herculean task to try and stitch together all the relationships and associations of the governance meta-model required to trace the correlations.In Figure 1, consider tracing program metrics for PII or GDPR impact. If you’re unable to modify your CRM suite to accept fundamental classifications or new fields in support of the governance model, then you will need an alternate way to connect the dots. This also applies to mapping specific data elements to corresponding policies.

Figure 1: CRM & Governance Meta-Model

If you’re trying to swim upstream, i.e. attempting to push metadata to sources, you may want to rethink this. It’s going to be expensive, time consuming, and require considerable resources for continuous care & feeding (think maintenance). Additionally, it’s likely to break applications and integrations.There is good news, however. Modern data catalogs can help solve this problem by providing a centralized place to build and document these meta-models, as well as the relationships and supporting content. If you get the right cataloging platform, it’s easy to build even the most complex governance meta-models without disrupting your data operations.

While modern tooling will help or potentially even alleviate your metadata problem, human change management challenges will still exist if you don’t tackle them head on. Why? A natural tension exists between stewardship and governance functions, and the people who practice them. Governance professionals often feel that the role of a steward should include delivering data governance functions. On the flip side, stewards want to focus on the health, viability and consumption of the data. To this point, most stewards I talk to are pretty sure that the governance overlay is likely to derail quality and usability efforts. While both perspectives have merit, the reality is that there’s usually a gravitational pull to one or the other.

We are seeing a confluence of these capabilities; this is part of what I reference when I speak of Enterprise Stewardship. On the marketing side of the similar conversations, you may have heard the notion that governance can come in two forms — offensive and defensive. The concept is that offensive governance is really focused on data usability through quality, health and freshness, while defensive governance focuses on the regulatory and compliance aspects — reporting, attestation, audit etc. While I generally agree with the premise, I still can’t get past my dislike for the term governance. Like it or not, the term has a negative or overly controlling connotation. I get it — that’s the point. However, I still feel that in today’s world where words are being co-opted to mean all sorts of new things, there are still some engrained perceptions, and one of those is that when people hear the term governance, they head the other way.From a people change management viewpoint, you’d be wise to address this. Thinking about the offensive/defensive perspective, I think the best approach would be to keep the two distinct. Enterprise stewardship keeps governance defensive and focused on GRC, while stewardship focuses on offense to drive data quality, literacy, observability, usage and and inter-operability improvements. Once you detangle the roles from one another, you’ll find each more empowered and able to begin the work of moving the mountain one rock at a time. This will help you to get the right level of curation of your metadata, in addition to the supporting meta-verse or catalog platform. All without the worry of undue bias skewing the program way or the other.

If you haven’t considered these risk factors related to effective data governance, it makes sense then to rethink your approach. Technology can best solve the aforementioned metadata problem, while the second issue of change management, or the “people” problem can best be addressed with parity between stewardship and governance.

In the words of the iconic band The Offspring — “you gotta keep ’em separated…”